Currently the children's shelves at bookshops are crowded with easy reads, straightforward linear fictions with near stock characters and predictable plots. They entertain their readers with the warming escapism of silly humour or vicarious adventure. Such books are not to be belittled. The young often need the comfort of the familiar, the readily accessible, and anything that gets and keeps them reading is of considerable value. However it is also important that young readers are sometimes challenged with more complex stories, ones that introduce them to the wonderful possibilities of non-linear and multi stranded recounts. Many specialists believe that interaction with such narratives - whether in the medium of print, film, TV or indeed video games - actively contributes to the development of complex cognitive reasoning. I can well believe it. I certainly think such processing adds significantly to our understanding of interrelationships, of life and people, of thought and time, and perhaps especially to our knowledge of ourselves.

So when a work of children's fiction comes along that is brave enough to eschew condescension and challenge its young readers with multi layered complexity it is to be most warmly welcomed. When such a book not only provides challenge and its consequent reward but is hugely enjoyable too, then it is a true treasure.

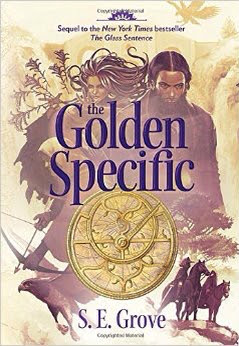

This certainly applies to US author S. E. Grove's ongoing Mapmakers sequence, of which Volume Two is now available here, albeit only easily sourced through online retail. I was enthusiastic about its highly promising first book, The Glass Sentence (see my post from Jan '15), and this second is, if anything, even better; long and complex for young readers, but very exciting not least because of the wildly original, wonderfully imaginative stimulation it offers.

Other reviews have compared Mapmakers to Philip Pulman's His Dark Materials trilogy (The Golden Compass in US). The two actually have relatively little in common in terms of plot, characters or themes. What they do share however is the fact that they create stunningly rich fantasy worlds, each the product of a unique and very special authorial imagination. Each work is grounded in a place that appears initially to be much like one in our own world (Lyra's Oxford and Sophia's Boston) but which soon turns out to be not at all as we know it. Each too then extends into a vast fantasy creation much of which is again both fascinatingly like, and at the same time totally unlike, our own world and its history. What I think it is fair to say is that S E. Groves's creation is shaping up to be the most originally imaginative children's epic fantasy since Philip Pulman's.

The Golden Specific continues to explore the world of The Glass Sentence, one based on a globe that appears to share our own geography but has been devastated by a fracturing of history that has left it divided into wildly dispirate time periods or 'Ages'. In fact the consequences of this are more fully and directly explored here than in the first book. Over and above their weird simultaneous existence, these various historical ages are significantly different from those of our own world. They do contain certain familiar echoes - such as the expansion westwards into 'Indian Territory' by the early US settlers, the Spanish Inquisition, the wearing of 'plague doctor' masks in 17/18th Century Europe - but they also feature events, people and objects that we would call supernatural or magical. Here are also worlds of different politics, different cultures, different belief system, all with characteristics both familiar and strange. However all are quite wonderfully conjured and given their own reality by this author's incredible imagination and masterful pen.

Like the classic middle section of The Lord of the Rings, this installmemt of Mapmakers is told as a split narrative; it consequently has the same totally compelling engagement and drive. Sophia remains the principal character and pursues her quest for her missing parents by travelling across the Atlantic to another era where she has to engage with a hostile 'Dark Age' and seek out a magically restorative village. Alternating is the story of Theo, the book's other principal protagonist, who remains in Boston battling an old adversary and trying to prove that Spohia's uncle is innocent of murder. Interspersed again there is also a flashback first person narration by Sophia's mother of the events leading up to her and her husband's disappearance. There are stories within stories too, accessed through the uber-reality of this world's very special maps, or narrated by other characters. It is a heady brew. Sophie's adventures are not only by turns high-adrenaline and grippingly intriguing, they are also often mystical, philosophical, magical, even poetic. In contrast Theo's escapades can be gruesome and frightening, but also at times light-hearted, amusing, cartoonish, even farcical. They counterpoint the story quite wonderfully and provide just the needed respite to the more lyrical and intense threads.

A fiction of such eclectic fusions could in other hands have so easily become a disparate mash of confused and disjointed elements. However it is a testament to S. E. Grove's masterly writing that she holds all of these strands together. She ultimately constructs an intrinsic, if complex, logic even though this only manifest slowly as the novel develops. However she also leaves enough space within her narrative for readers to weft their own imaginative and cognitive bindings between the tale's multiple threads. It is actually this last skill which is probably the strongest indicator of her genius - and I do not use the word lightly. It is in these self-realised potentialities that the reader's greatest involvement lies. That involvement is, in consequence, as deep and multi layered as the narrative.

At the start of Chapter 34 the author writes this stunning passage. It is one of those rare 'Yes!' moments in reading that stopped me in my tracks and filled me with astounded admiration.

"Sophie had no notion of time passing. She was not entirely sure of where she was either. So completely had she submerged herself in the memories of the beaded map, she felt as though she had lived a year in Alvar Cabeza de Cabra's skin. She had seen the parched, harsh world as he saw it, grieved its losses as he grieved them, felt the feeble thread of hope given to him as he felt it. Somewhere, like a distant echo, she felt these things as Sophie, too."

In describing so poignantly Sophie's engagement with a magical map, S. E. Grove could not have better expressed the reader's experience of a rich, engrossing and evocative narrative like The Golden Specific. Such is this writer's astounding power of imagination and her command of language, thought, feeling and narrative that she magically creates for her audience just such a multi sensory, multidimensional map as she has invented for her characters.

Whilst, by the end of The Goldn Specific most immediate goals have been reached, much inevitably remains unresolved, and Theo's plight is nothing if not desperate. On finally closing the book readers will I'm sure be in an ambivalent position, thrilled that there is more to come, but devastated at the prospect of having to wait for it.

The very best stories are true even though they are not real. This applies strongly to this one. S. E. Grove has found human truth in wild fantasy and that is a very special talent indeed. The so aptly named Mapmakers is already a truly wonderful work, and a profoundly important one. By the time its third part is added I think there is every chance that it will prove to be one of the great works of children's literature of any age or clime.